- More Than Four Questions

- Posts

- Question 5: What do we do about the cost of Jewish living?

Question 5: What do we do about the cost of Jewish living?

An Elul Reflection on the difficulties of socioeconomic exclusivity in progressive Jewish life and what we can do about it, even if it feels awkward

“Jewish life is expensive,” my colleague shrugged with something of a wince. We were talking about a local mikveh in Manhattan— the only mikveh in the city that allows non-Orthodox conversions. The price for a conversion dip, already out of reach for many New Yorkers at $360, had just gone up to $500. When you combine that with the several hundred dollars to take a conversion course, plus the typical expectation of joining the synagogue where one is converting, becoming Jewish can easily cost thousands of dollars. Even for synagogues like my own with “Fair Share Dues,” and the unofficial stance of welcoming members at any level of contribution, synagogue affiliation can be more than a little intimidating.

And then there’s the cost of Judaica. Things come with a range— you can easily get a tallit for under $100 and a cheap Hanukkiah, and, well, if you’re in Manhattan you’ll never need to buy Shabbat candles so long as you’re perceived as female and Jewish and take a stroll by Chabadniks every Friday (boy oh boy could I/will I one day write about the joys and massive problems with that). But, often, folks want nice Judaica, and nice Judaica costs a pretty penny. As an example, my own tallitot each cost upwards of $300, the claf (kosher scroll) for my mezuzah was $50, and the seder plate we got from our wedding registry was over $200. There’s a lot of wiggle room in what constitutes Judaica (one year I improvised a seder plate from an IKEA platter with soy sauce dishes around the edge holding each component), but, particularly for Jews who are newer to Judsaism and/or Jewish practice, it can feel important to have access to items crafted specifically for Jewish life. And of course, if you’re purchasing kosher food for your dishes, you can expect your grocery bill to be higher.

For folks raising kids, there’s also the cost of Jewish education, from weekly Hebrew school to private B Mitzvah tutoring to summer camps to day school (which in NYC can easily run $30k-$50k+ per child without tuition assistance). Even for families that “only” do religious school and B Mitzvah tutoring, the financial impact can be significant and off-putting.

All told, we have to be honest with ourselves: the cost of doing Jewish keeps many Jews from being able to afford Jewish life. And we have to be even more honest with ourselves: while most halakhically-driven Jews will prioritize Jewish engagement as much as they can whatever the cost, many non- and post-halakhic Jews will not. They’ll leave the shul they joined when they were young (or never join in the first place), they’ll outsource hosting Jewish holidays to their parents or grandparents, and over time their engagement in Jewish life will wane.

We fret, so very often, about how progressive Jews are becoming less committed to Jewish institutions and less interested in Jewish community in general. A lot of demographers like to blame intermarriage, and I’ll say the same thing about that as I’ll say about the money: the issue is access. When interfaith and multifaith families don’t feel welcome in Jewish spaces, they won’t prioritize entering them. And when lower socioeconomic families (or heck, at this point, middle/upper middle class families) don’t feel that they can afford Jewish spaces, they won’t prioritize entering them.

So what do we do?

Here’s the obvious and maybe a bit awkward answer: we ask the people who can afford to pay to give a good deal more, and we charge the people who can’t afford it a good deal less.

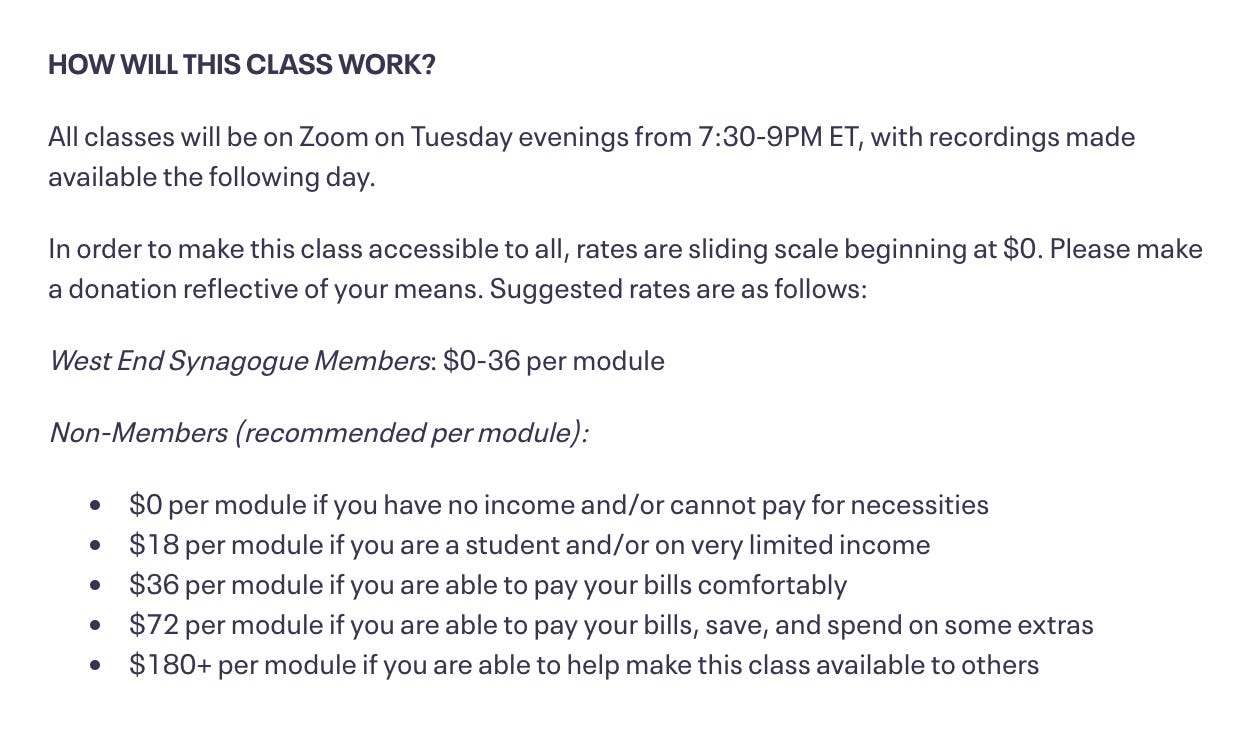

When I ran Gan (an online intro to Judaism class) a couple of years ago, I did so with a pretty radical sliding scale, asking participants to pay anywhere from $0-$180 a module. But I didn’t just ask folks to pick a number arbitrarily based on what they thought they could afford. I offered somewhat measurable guidelines to help people determine what to pay. And they worked. I had people in the class paying nothing, and people paying more than full price.

These days, I use a large sliding scale for lifecycle officiation honoraria, asking folks to consider what they can afford based on their overall finances and their budget for their baby naming/wedding/etc. While once in a while I find that someone pays me less than seems to be reflective of their means, generally I find that the people who seem to have more give more, and the people who seem to have less give less. This is as it should be.

A lot of sliding scales, I’ve found, only consider income and family size. That’s a great start but not in my opinion a proper way forward in a society with massive debt and a centuries-old system of racist, patriarchal inherited wealth. If you and your neighbor bring in the same income, but one of you has student loans and the other has a trust fund, you should not be paying the same price for synagogue membership. And if you’re thinking “Ok sure but how far does this go? If I have more money should I be paying more for the subway or for food than other people?” then I would say, actually, yes. Actually, those with more, to some degree, should always be subsidizing those who have less until those who have less can afford a basic quality of life, and for Jews that basic quality of life should include access to Jewish community.

I mean, seriously, what would it look like in Jewish life if the richest, let’s say 10% of the Jewish community, gave enough to make a year of Hebrew school $100 even in the wealthiest city in the USA? $100 is still more than some families can afford, but it would put Hebrew school in the reach of so many. What if they gave enough to make it possible for those with low income and low wealth to have completely free synagogue membership? What if those who could afford it actually tithed in the way that our ancestors did, giving one tenth of their income to the Jewish community?

The irony in this whole discussions is that the stereotype of Jews as rich, miserly moneylending types is among the most virulent antisemitic tropes out there. We carry in our cultural DNA a myth of massive wealth, a story that is so utterly unreflective of most of the Jewish community throughout history. Just as we have always been a multiracial, multiethnic, and yes—multifaith—people, we have always been a people with a huge socioeconomic range. Many Jews do not have wealth and never have, but for those who do, there is a massive opportunity right now to step up.

If this were to happen, institutions would have to step up too. We’d have to think carefully about how to allocate the money so that it served those most in need in the moment and also fortified the center for the future. We’d have to find the balance between subsidizing membership and replacing the literal or figurative carpet. We’d have to learn how to budget according to our values, and to bring our values in alignment with a financial reality that no longer need be based in scarcity. Doors would open in so many ways.

Look, we don’t have to dig deep to find the reason for all of this. The inclusion of those with less is brought up again and again in Torah. Just two weeks ago we read the words in Deuteronomy 15:10-11:

There may never cease to be needy ones, and there may never cease to be wealthy ones. But we have the opportunity to step up— if we have wealth, by giving, and if we are a part of institutions, by asking the wealthy among us and around us to give more generously. Whatever our starting point, we can work for a world in which all of us can afford to engage fully in Jewish life. And that, my friends, is good for all the Jews.

Reply